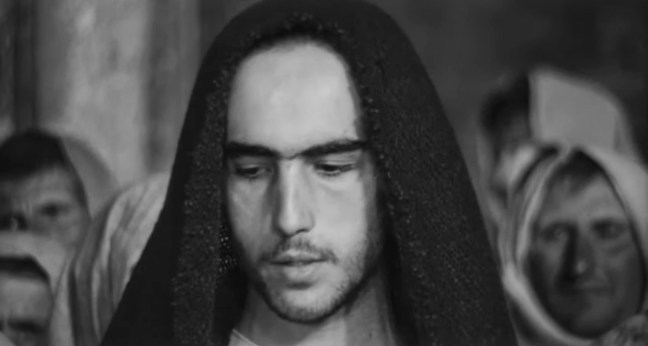

’Perfect Days’ – by Wim Wenders (with Koji Yakusho)

.

“All my films deal with how to live.”

~ Wim Wenders

.

Why do we watch a movie or enjoy any piece of art but for the joy, happiness, or relief we derive from such activity? Well, sometimes we use a movie not so much to feel, but rather to stop feeling. We want to be alleviated from our sense of boredom, or be distracted from our constant worry, or have the lowest ambition to be rewarded with pleasure, plain simple pleasure which, if not delivered, will make us move on to something else. Film as an art form is ambiguous, for it has in itself an entertaining power which makes it the prey to our most suspect desires. Well, Wim Wenders, in this movie, wasn’t going to give way to that ubiquitous trap and fall. With ‘Perfect Days’, he made a movie in which there is no desire to be had, which offers no suspense, no excitement, no resolution of any kind, but from which you would never want to move away. A movie that describes the quiet, plain, orderly living of a man whose job is to clean public toilets in Tokyo.

Hirayama lives each and everyday as if it was a perfect day. For him, there is no possibility of failure in life. And he makes sure that boredom is an impossibility. So he cares. Hirayama cares about everything he does, and seems to be profoundly related to his modest home, to his morning toilet, and to the watering of his plants. He does what he has to do, with no judgment or resistance. He doesn’t mind. He feels his inner freedom. He has everything he needs, so he smiles at life and life smiles back at him. He breathes when he steps outside and looks at the sky as for the first time, the wonder of it all. Then he buys himself a can of coffee from a local vending machine, opens his van, sits, drinks a sip, chooses a song from a bunch of cassette tapes, lights the engine, drives, and listens to ‘The House of the Rising Sun’ by The Animals. For that’s where he is now, in the house of the rising sun, going to his work through the sprawling suburbs of Tokyo’s morning, undisturbed, confident, present.

[…]

A reflection on the film ‘Perfect Days’ by Wim Wenders… (READ MORE…)

.