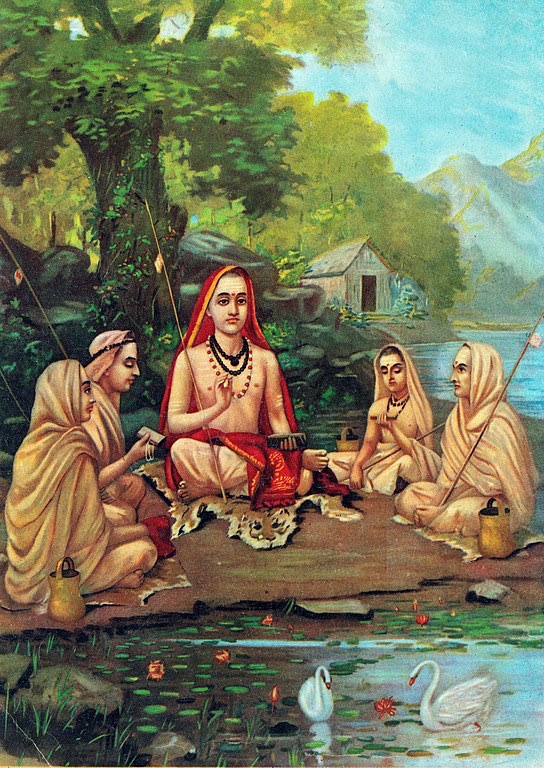

Hampi Vijayanagara, Karnataka – India

We are always too late with our identity. We come after. We experience something within, a sensation, an unease, a thought, and then say: I am that. We start from what happens, from experience, out of which we draw some identity. We are lazy. We identify with what comes. We experience our body, and draw the conclusion that this body is what we are at the deepest level. And then we live from there, from this conclusion, from this belief, this concept of ‘me-my-body’ — which we refer to as ‘I’. Our chance has passed. We have drawn comfort in that conclusion, but have invited its many companions of voyage too, which are suffering, fear, lack, and the likes. We have given ourself to the wind of arbitrary experiences. We depend on everything that passes uninvited. No wonder we suffer, finding there no stability, and no peace. We are at the mercy of what comes. So we are desperately trying to shape what comes, in order to shape our identity, and derive from it some elements of happiness. Hence our constant striving, seeking, debating with life, struggling with what we are, and with what the world brings.

We think that all the responsibility falls on us, that we are the designers of our identity. We are little ghosts exhorting themselves to happiness. And every time we fail and fall from this imaginary pedestal, we head for another direction, another hope, another expectation, and so goes our life — dependent and miserable. Until we finally listen. Until we see that there is an identity before any experience of body and mind. It isn’t that difficult to see and understand. This is only logic. This is, as Swami Dayananda Saraswati used to say, Vedantic logic: “Vedantic logic and worldly logic are diagonally opposite. Worldly logic is: ‘I experience sorrow; therefore I’m sorrowful’. Whereas vedantic logic is: ‘I experience sorrow; therefore I’m not sorrowful’.” So we have to go further back, and it takes some courage. For we are so gullible. We don’t have any true, reasonable stand. Yet, the way we speak betrays our intuition that we are not fully identified with our body and mind. After all, we constantly comment on them. We are not fully implicated. We put ourself at a distance from our own identities, but don’t go far enough. We stay somewhere along the way, as a self separate from it all. We don’t finish the journey. We don’t look well enough. We presuppose we are something, a somebody, a person, and leave ourself there, close, so very close from a higher, nobler truth.

Cannot there be an experience where ‘I’ is really, truly ‘I’? Where ‘I’ cannot be projected or conceptualised? Where it is not belittled, depreciated? Where it cannot be coloured, biased, conditioned? Where it is here in ourself, as ourself, like a pure, unalloyed, super subjective identity which is like a tower in our life, knowing everything that comes without having to be anything, without drawing an identity from it? And experiencing every single object of body-mind-world while staying itself unaffected, unaltered, and whole? After all, when we say ’I am depressed’, what we really say is that ’I’ is ‘depressed’. ‘Depressed’ has become my new identity. So ‘I’ is being repressed, suppressed for a while, replaced by ‘depressed’. But the good news is that if there is an ‘I’ that can be depressed, this same ‘I’ is here standing before the state of being depressed. There is a being before being depressed. We have let ourself being coloured, forgetting that we are in fact that which is here to be coloured. We have lent ourself to the first coming visitor. But the Vedantic logic is here to remind us that when depression is on us, or affects us, it only hides our true identity for a while. It conceals us but doesn’t change us. We stay what we are — a being untouched — depression being only what clouds us for a time. There is something here under cover, a reality, a presence, an aware being that is only being itself. This being can never be touched by depression or sorrow. What is touched by sorrow is a belief, an idea, a projection of ourself as an entity that can be affected by the passing weathers of life. Meanwhile, this pure, innocent being that we are, and that is our one only identity, stays on, living its life of being only being, while a non-existing self is playing depressed and being melodramatic.

.

~~~

Text and photo by Alain Joly

Quote by Swami Dayananda Saraswati (1930-2015)

~~~

.

Website:

– Dayananda Saraswati (Wikipedia)

Suggestion:

– Other ‘Reveries’ from the blog…

.