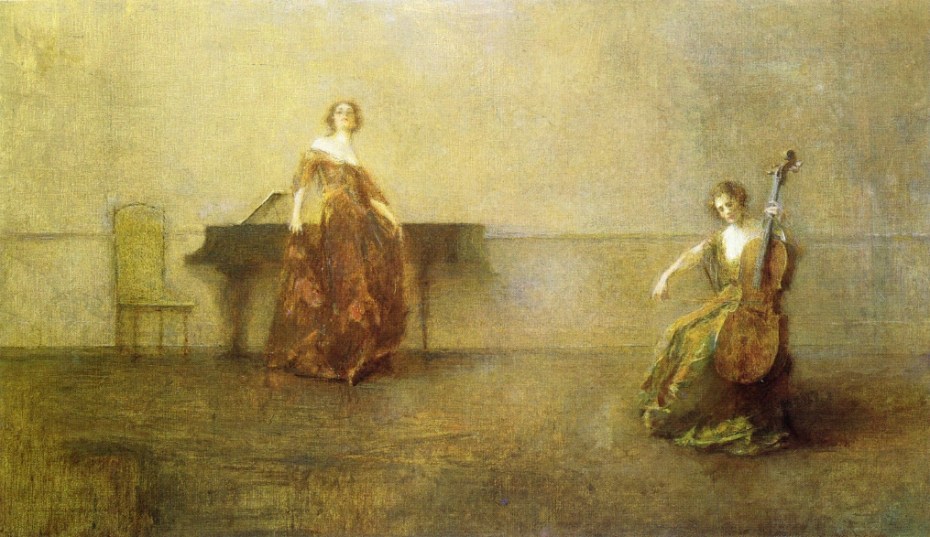

‘The Song and the Cello’ – Thomas Dewing, 1910 – WikiArt

‘The Song and the Cello’ – Thomas Dewing, 1910 – WikiArt

There is a prayer that was once addressed to our deepest self. This is a song of mourning for the life that we cannot get hold of, for the self that we cannot truly be. This mourning is the story of our wrestling with life, of our puny self, a self that is elusive, fragile, fearful, and has been plagued with suffering. So this prayer is a plea addressed to the one that can save us from our intolerable pain. But it is not intended to God. It is intended to ourself, to that part of ourself that appears to be soft, uncertain, constantly seeking affirmation, but is in fact holding the key to the peace we are so desperately looking for.

This self is called, in the Christian tradition, the ‘lamb of God’, and refers to Jesus as ‘Christ’. It is the one for whom John the Baptist had this exclamation: “A man who comes after me has surpassed me because he was before me”. (John 1:30) This self is called a ‘lamb’ because it is destined to die in the embrace of being. Being is its only reality, its rock-like ground and certainty, the one that ‘surpassed me’ because it was ‘before me’. The self that we believe ourself to be is a fragile construction, and a vulnerable entity. It is afraid of dying, of having no solid ground, and is pleading for one.

“Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.” This plea is a liturgical prayer used in every Catholic Mass, borrowed from a passage in the New Testament (John 1:29). This prayer, called in Latin ‘Agnus Dei’, was used by many of the greatest composers for a number of choir pieces. In 1967, an American composer named Samuel Barber, at the time battling with depression, decided to adapt his 1938 ‘Adagio for Strings’ into a choral work. His ’Agnus Dei’ is a gorgeous expression of a longing for God, a longing that is the one longing of all humanity, the desire for peace, the unceasing quest for a happy living.

The song begins with a long exposition of pain, a soft melody that undulates, escalating, softly seeking for a resolution. It is mourning for the lost completion that we have looked for in thousands and thousands of ways. History is but the story of this longing, of the many ways each and every human being has strived for a relaxation of this tension towards happiness. The chant is a plea, a plea to the lamb of God, to the one that God has brought on the altar to be slain; the one that has in its hand the key for the release of suffering from the prison of the apparent self. That one can save us, it is said. But who is this one but ourself?

There is a sense of lack that is gently being played in the background of our lives, something that we try hard to cover up. But it is here nevertheless, a straight line of longing that constantly reminds us of our vulnerability, like a stubborn accompanying tune. So we try to cover it up, always, again and again, cover it up, cover it up. And this covering up has become ourself, what we are. It has developed into a self, a chief commandant whose duty is to fill the gap of sorrow contained in this throbbing, unabated air. And this melody of our life is growing louder and louder, an unquenchable desire to be released, riveted to our being.

The song is clearly looking for a resolution. It eventually finds it, high above the mind, crystal clear behind the plea, settled in itself, high pitched in its purity, its untouchability. The resolution is what appears when the self we have invested in all this time is discovered to be not here. That’s how you slay your self, by recognising its not being here, by uncovering the illusion of its existence. That’s how you ‘take away the sins of the world’, by releasing the beliefs and actions whose only purpose is to validate and consolidate this illusory entity. And that’s how you receive mercy, by recognising your true identity as simply being.

So if you want to slay suffering, you simply have to slay the one that claims to be suffering. It is as clear as day. We have to find it, that sufferer. That’s the whole search laying itself bare in front of you: to drive the sufferer out of its hiding place, to force him to show himself, to gently invite her to voice her name, who she is, why she is here at all. That’s the highest investigation you can conduct. Find that suffering self and know its true identity. In other words, you need to really know yourself. Then you may see what happens, what is that supposed self actually made of. “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.”

Twice in the piece, the melody is travelling along this line of longing, finding its ultimate resolution as the fullness of being. The second time, the longing is less pregnant, mixed with accents of profound joy, its pain pierced by the transparency of understanding. This repetition is the expression of what Rumi meant when he wrote: “Flow down and down in always widening rings of being.” The suffering loses its grip with the loss of the one that owned the suffering. The longing finds, in itself, the object of its longing. So the longing is being eased out, and so is the suffering, replaced by the peace contained in our own, unencumbered being.

The voices in the choir then stumble twice on a stretch of silence, attempt to resume their longing activity, but are unable to do so. The longing has been slain, and is now only expressing the peace that it had been veiling. The tension comes to a rest. We are now left with a pure, swollen sense of being. The choir voices have blended to form a low, unending, majestic river, imbued with the peace contained in it. Any remaining longing is now soaked with peace, confident, and is experienced as a celebration of the quiet joy that the longing was aiming at. All suffering has now come to a definite end. “dona nobis pacem”. Resolution done.

So my lamb, my puny self, grant me the peace hidden behind my illusory existence. Show me not the lamb as a lamb, but the lion that has triumphed over it and that was its true identity. The lamb was never that fragile entity. It was pretending to be, and its pretension had put the lion to sleep, preventing its peace to rise as the very essence of life. There is a tension of pain running along the whole choir piece, but this tension now finds the resolution it was seeking. This resolution is peace. The peace that stands at the core of any suffering, that is its raison d’être. “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant us peace.”

.

~~~

Text by Alain Joly

Choir Piece by Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Painting by Thomas Dewing (1851-1938)

~~~

.

Listen to Samuel Barber’s choir piece ‘Agnus Dei’ performed by the Choir of Trinity…

Websites:

– Agnus Dei (Barber) (Wikipedia)

– Adagio for Strings (Wikipedia)

– Samuel Barber (Wikipedia)

– Thomas Dewing (Wikipedia)

.

Back to Pages

.